READINGS: SHY; The Alarmingly Outspoken Memoirs of Mary Rodgers

Rodgers & Hammerstein & Rodgers & Sondheim & Guettel & How I Lived & Loved Musical Theatre

I am assuming if you are reading me you already know what you’re in for, but, on the slim chance you came here via Google or following a friend’s link, know this: My appreciations of books are all tied up in autobiography. Reading is personal, always, and books that move you do so because they are relatable to you. I write about those connections. And often a post is more me than book. I’m not a literary critic. I’m a reader who loves books and writers and sharing stories with others. You’ve been warned.

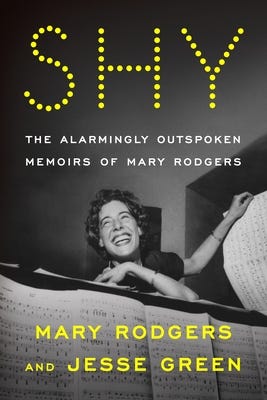

In this post I talk about 1SHY: The Alarmingly Outspoken Memoirs of Mary Rodgers, by Mary Rodgers and Jesse Green, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, August, 20222

The first live musical I ever saw was a high school production of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s CAROUSEL, in which my sister, Peggy, was in the chorus, and my brother, Leo, played Jigger. I was seven years old. My mother drove and on the way we picked up my aunt, Sissie, who was paying for the tickets and was in charge of all things theatre in the extended family; most famously she took each niece and nephew when they turned 12 to New York City, where they stayed at the Taft Hotel, ate at Schraffts, and went to see the Rockettes at Radio City Music Hall, and as many Broadway musicals as Sissie could cram into the trip.

I started asking when I could go to Broadway as soon as I knew it was where people sang and danced and played pretend, and bonus, New York was also where all the famous writers lived, mostly at the Algonquin. New York — which I later learned meant only a few blocks of Manhattan when we talked about it — was mecca for me from birth, or so it seems now; I cannot remember a time when I did not think it was where I belonged, where I was the most me I could possibly be. As soon as I got there that first time, and every time since, I have been embraced by the feeling of “I’m home.” It’s where my heart is.

So, this high school CAROUSEL was a huge deal. It would get me one step closer to my dream city. I remember that I was all gussied up in my Easter clothes — Sissie believed that you “dressed” to go to the theatre — and she was in a red checked pencil skirt dress, very Katharine Hepburn in SUMMERTIME. Sissie was fond of changing Katharine Hepburn’s STAGE DOOR line: “The calla lilies are in bloom,” to “The forsythia are in bloom,”3 since those yellow blossoms meant spring had arrived and her bedroom in the nearly heat-less ancient home in which she lived with my grandfather and grandmother would no longer require she wear multiple layers of sweaters until she got into the bed, under her much loved electric blanket.

The high school auditorium was a cafeteria during the day, but it had a “real” stage, a proscenium with a curtain, and the seating was first come, first choice. My mother and Sissie chose seats about midway back, but I saw that the first few rows were nearly empty and asked if I could move up there. My mother said something along the lines of “stay where you are” as Sissie simultaneously said “I’m sure it’s fine” and up to the front I went.

I was enraptured. From the moment the orchestra started the overture and the curtain opened on what I took to be a carnival, and right there on the stage, a real carousel! And my sister walking around pretending to talk to another girl, and my brother running through causing some sort of uproar, and Peggy’s best friend, Shirley, who was playing Carrie Pipperidge — the role Peggy had wanted — and it was everything. EVERYTHING. And then SPOILER ALERT Billy died.

I was not prepared. Judy Garland and Esther Williams never died in musicals. I lost it. I wonder now what the audience thought about a seven year old boy who was sitting all alone in the first row of a high school cafeteria/auditorium sobbing, heaving, saying “Oh no, oh no!” Sissie came down and sat beside me, and told me, “It turns out fine. He gets into heaven. Though I don’t think he really would.” As we were leaving the theatre, my mom took me aside where Sissie wouldn’t hear her and said, “I will NEVER take you to another show as long as I live.” And she didn’t. Although she did end up chauffeuring me to and from many rehearsals and performances, and about ten years after the CAROUSEL sobbing episode, it was my mother who was audibly crying in an audience, watching me on stage in my first lead role, my first singing role, for which I was crucified on a chain link fence wearing a Superman t-shirt. Later, after the show, though at that point in our lives we had little use for each other, she said, “I didn’t know.” And I, being the ever gracious sixteen year old I was said, “I’ve been telling you forever.”

I was not a pleasant adolescent. Neither was Mary Rodgers. And we both are happy to own that. If you’re harboring some illusion that Rodgers and Hammerstein led uplifting, musical hero lives, don’t read this memoir. Richard Rodgers was a letch, a cold fish, an alcoholic, and those are some of his better qualities. And his wife, Dorothy, Mary’s mother, was equally awful. It’s some sort of miracle Mary survived her upbringing with any sort of emotional and psychological balance at all, but she didn’t just survive, she thrived.

And while this book is a lot about musicals and an era of them much missed (or, at least, the idea of how we imagine it to have been is much missed), it is even more about the journey of a person to self-awareness and independence, to her own strength in the face of myriad obstacles — lousy parents, lousy taste in men (more than once), lousy marriages, the death of a child, working in a world where women were a rarity, self doubts and lack of confidence in her talents. And yet, proof of her guts and humor, she who says repeatedly she almost never cries, there is not a maudlin or self-pitying moment in the entire four-hundred-and fifty-plus pages.

I loved this book from beginning to end. It is filled with juicy theatre-insider gossip, not the least of which items are her near constant (and hilarious) jabs at Arthur Laurents. Frank, blunt, and open, to read Mary Rodgers feels like talking with a particularly erudite and informed friend, and learning all sorts of new things about all sorts of things you thought you already knew all about.

Mary was friends with Stephen Sondheim from the time they were both children. He spent much of his youth with Oscar Hammerstein, who mentored him, and Mary spent most of her life being in love with him; a relationship that caused some angst for both of them and which remained unrequited in the physical sense, but one does get the feeling by the end of the memoir that regardless of whether or not there was a sexual element, Sondheim was the love of her life.

Hard to imagine being the daughter of Rodgers of R&H, and besties with Stephen Sondheim, growing up in the midst of genius and musical theatre royalty, and still having nerve enough to attempt to write your own musicals. Equally hard to imagine not trying to do so. Mary did. And with some success, that being ONCE UPON A MATTRESS.4

The sections about MATTRESS are fascinating. It began as an extended skit of a musical for a summer camp and through serendipitous circumstances was expanded into a full-on Broadway (though it started Off-Broadway) show. Originally intended as a vehicle for Nancy Walker, when George Abbott begrudgingly came on as director he wanted a new face he could turn into a star, and that’s how Carol Burnett got her first Broadway show. At the 1960 Tony Awards it was up against THE SOUND OF MUSIC, and FIORELLO! — which won in a tie — as well as a Jackie Gleason vehicle, TAKE ME ALONG, and GYPSY5. George Abbott won for best direction of a musical, but NOT for MATTRESS, rather, for FIORELLO! And in the incestuous, small-town-ish world of musical theatre that is revisited over and over in this memoir, those Tony awards saw Mary losing to her father, and competing with him and Sondheim.

MATTRESS is still produced regularly by high schools and community theatres6, and was still bringing Mary about $100,000 worth of royalties a year when she was alive. Not bad for a summer camp musical.

And prior to reading this memoir, MATTRESS was about all I knew of Mary Rodgers except that she was Richard Rodgers daughter and Adam Guettel’s mother and had written THE BOY FROM… with Sondheim. I had no idea she’d written the FREAKY FRIDAY novels, nor that she’d had such a career in philanthropy.

But SHY isn’t all about Mary. There are stories about Sondheim’s MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG debacle. And acknowledgement that it has become an obsession with lots of musical theatre types7. Mary seems ixy/nixy on whether or not the character of Mary in the show is — as musical theatre gossip legend would have it — based on her, but just recently, proving the ongoing obsession with the show, there was a documentary about the original production, directed by Lonny Price, the original Charley Kringas. And the original Mary, Ann Morrison, has an entire cabaret evening about the show, for which she was told as she was learning the role to think Mary Rodgers, because that’s who it was based on. So, there’s that. I owned at one point the cast recordings of every version of MERRILY available and I saw it repeatedly, every time a production happened anywhere near me. The Kennedy Center Sondheim Celebration production had the perfect Gussie in Emily Skinner, and as Charley, Raul Esparza was other worldly good; his FRANKLIN SHEPARD, INC actually stopped the show. I have rarely seen anything as intense, hilarious, heartbreaking, and beautifully sung all at once in my many years of theatre going.

She also visits her father’s later years, and numerous flops, including one she talked Sondheim into doing with him, ANYONE CAN WHISTLE. I think the saddest of all of them was I REMEMBER MAMA. Sissie and I saw it together in New York and we were both flabbergasted. We were not the kind of people who had EVER expected to HATE a MUSICAL, but that broke us.8

The point I’m trying to make — circuitous though the route may be — is that Mary Rodgers and Jesse Green’s SHY is a must read for any musical theatre fan. I know I spent lots of time during this post telling stories about my life prompted by Mary’s memories, but it seems to me you can’t have loved and/or been part of musical theatre — no matter how far on its outskirts — without the people and events and shows and places and music in this memoir having been part of your life too, having resonance in your life.9

And sitting with Mary and Jesse, it’s like having met the most insider, hilarious, forthright duo who regale you with anecdotes and history you’d never have known otherwise. I loved it. And I wish I had known her, and knew him, and gotten a chance to ask questions about things the lawyers wouldn’t let into print.

Five stars. Or, endless stars and eleven o’clock numbers. Loved it.

But enough about me, lol, and thank you for sticking with me and here we are, going.

Full Disclosure: I was sent a free copy of SHY by Rose Sheehan of FSG books, requested from her by another publicist I know. There was never any discussion concerning me writing about the book. I doubt Ms. Sheehan even knows I have a substack.

SHY: THE ALARMINGLY OUTSPOKEN MEMOIRS OF MARY RODGERS is published now, eight years after her death. The project began as an autobiography that Mary had asked the writer, Jesse Green, to help her with. He had hours and hours of tape and interview and SHY is the result of that time. The book is a double thrill because while the main text is in Mary’s voice, almost every page has footnotes by Jesse which supply background information about names and connections we might not know, and details Mary didn’t tell. I have modeled this post on that format. There’s the main text, and then these footnotes full of asides and connections you definitely wouldn’t know, because I’m not famous.

I spent much of my childhood with Sissie, the best of my childhood with Sissie, which is a long story to do with my mother having been widowed with six children under the age of 14, and my early detected precocity (i.e. I was a big ol’ girly-boy) was such that Mommy knew Sissie was better equipped to nurture and mentor me than was she. Sissie had never wanted to be on the stage, but in college she had taken Dramatics, and she many times told me the story of this exercise they’d been given: Each girl (and it was only girls, as she went to the women only Notre Dame of Maryland, run by the School Sisters of Notre Dame, a school to which she was only allowed by her soon to be senile and already controlling mother to attend because her fraternal aunt after who she was named, Sister Marie Frances, was president) was tasked with saying the line, “Are you the gardener?” in a manner that told an entire story of who she was, where she was, and what she wanted. Sissie, the first time she did it for me, actually seemed to have become another person; suddenly “ole made ant” as she had come to be called for some reason by some of the relatives — never by me — became a stunningly provocative grande dame, with an edge, sort of early Hepburn and later Bacall. She told me the teacher suggested after that exercise that she pursue dramatics. I was fascinated and asked her to do it many times through my childhood. And years later, when I was teaching acting, I gave the exercise to all my students, and never changed the line, “Are you the gardener?”

ONCE UPON A MATTRESS was the show my sister and brother’s high school did the year after CAROUSEL. The lead, Princess Winnifred the Woebegone, was played by my sister Peggy’s best friend, again, she who had played Carrie in CAROUSEL, Shirley. It was their senior year and Shirley’s parents moved away — I can’t remember where — and she was deeply in love with her high school sweetheart and so, for the end of the school year she lived with us. To me, having the lead of a musical living in my house — I couldn’t have been any more breathless and excited about it had Shirley been Streisand herself. Whose records, by the way, Shirley had all of and it was the beginning of my Streisand obsession. I mean, granted, being as model gay as I already was, I’d have gotten to Streisand on my own, but Shirley helped me along. And, funnily enough, decades later when Streisand was on a late in her career tour, and I had sort of a real job (but in the arts, and you know how that pays) I got a $750 ticket so I could see Barbra in person before she or I died. I don’t regret a penny of it. We were tenth row. So close. It was amazing. And, as we headed for the D.C. Metro to take us back to the station at Shady Grove where we’d parked, from the crowd of thousands pushing toward the trains, I heard someone say, “Charlie? Charlie Smith is that you?” It was Shirley, and her high school sweetheart husband, over 30 years after she’d been the diva living in my house. And here’s life for you, readers: I asked Shirley, “Do you remember how you played your Streisand albums for me that time you lived with us?” And she said, “Oh, did I really? I don’t remember much about that time.” Milestone for me. Didn’t even register for her.

How does GYPSY, widely considered to be one of the best musicals ever written, lose to anything, let alone the treacly THE SOUND OF MUSIC? And how does Ethel Merman as Rose in GYPSY lose to Mary Martin as Maria in THE SOUND OF MUSIC.

I contributed to Mary’s royalties. When I had a theatre company, the mission of which was to give high school age students the opportunity to do full productions in casts which included experienced adult actors, I produced and directed ONCE UPON A MATTRESS. It was one of the easiest shows I directed; easy in that its construction lends itself to smooth flow and it’s all fun all the time, which, with hormonal teens, is definitely the way to go.

I also directed a production of MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG, which I had wanted to do since I began directing. I badly miscast Charley but had a gloriously sung and acted Mary, an intense and sort of terrifyingly focused Franklin, and a heartbreaking and a bit crazy Gussie. And the ensemble! I loved it. But, the MERRILY curse continues. We had to cancel performances because of a blizzard, and there was no way to make them up. I lost tons of money, but, as with the Barbra Streisand tickets, I don’t regret a penny of it. I opened the show with the stage a mess of all the props and set pieces that would be used throughout the show — since it starts at the end, when the friendships are destroyed — and my Franklin walked out on stage and hit a single note on the piano … and that started the overture during which the cast put the set in place and segued into singing MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG. I thought it was genius. Which was a good thing. Because no one else did.

Liv Ullman was so egregiously miscast as to be painful to watch and pitiable. It did not help that on that same trip we saw Angela Lansbury and Len Cariou in SWEENEY TODD, Robert Klein and Lucie Arnaz in THEY’RE PLAYING OUR SONG, Carole Shelley and Philip Anglim in THE ELEPHANT MAN — Liv Ullman didn’t stand a chance. FYI: We later saw her in a production of ANNA CHRISTIE and left at intermission. A first for us.

And believe me, much as I’ve blathered on about myself and footnoted, I didn’t mention all my connections to shows and stories told in SHY. I also directed productions of CAROUSEL and SOUTH PACIFIC. I directed GYPSY twice (and failed both times.) As far as Sondheim goes, I was in WEST SIDE STORY (I was dreadful — picture Riff made up like a drag artist. We made parody lyrics for cast parties and at WSS one was something like: “When you’re a Jet/You’re not het, no you’re gay/You’re not top/You’re a bottom and terribly fey” — you get the picture.) I was Sweeney in SWEENEY TODD (and got a glowing review, I might add, from a Baltimore paper — and also had temporary anorexia. I fancied myself a method actor and it seemed to me that if Sweeney had spent all those years in a penal colony, he would have been malnourished to the point of starving. My diet during the show was one can of tuna every two days, followed by a laxative, and as much celery, water, and coffee as I wanted. I’m not sure how I survived it.) I was the Father/Narrator in INTO THE WOODS. It was the show that made me decide I was too old to act. At a rehearsal, past the time when we could call for line, I got super pissed because mid-scene there was this gaping silence and I was sure it was another of the irresponsible equity candidate young whippersnappers who’d been drinking and drugging every night and fucking up the rehearsals. The silence went on and on and on. Finally, the dear sweet stage manager, who I’d known for years, was told by the dear, loving director — who made be better in any show I did with him than I was in anything I did with anyone else — told the stage manager to give ME the line. It was mine. I was blanked. No idea at all. I knew it was time to quit. But long before that and long before Marianne Elliott got permission to gender-switch COMPANY, I was in a production as Marta - changed to Marti. I killed with ANOTHER HUNDRED PEOPLE, and I loved singing it, but I loved even more her lines. The “dress all in black, sit at the end of some bar, drink, and cry. That is my idea of honest to god sophistication.” Damn, that was fun to do every night. I’m sure there are others I’ve missed but, as with my turn in INTO THE WOODS, there are places in my mind where things used to live that are now just echo chambers. Nothing there. I hesitate to make the old actor story worse, but, right before WOODS opening I sprained my back. Between scenes, backstage, I had to stretch out flat on the ground. And I was assigned a watcher (a few, actually) to make sure I got up off the ground and to my next entrance, which was usually on the other side of the stage or through a hole in the floor or atop a tree. Yes, it was time to quit. Time to say, as it is with this post, Here we are, GOING.

I love your in-depth coverage & completely agree that all musical theatre lovers MUST read…as she doesn’t hold back.